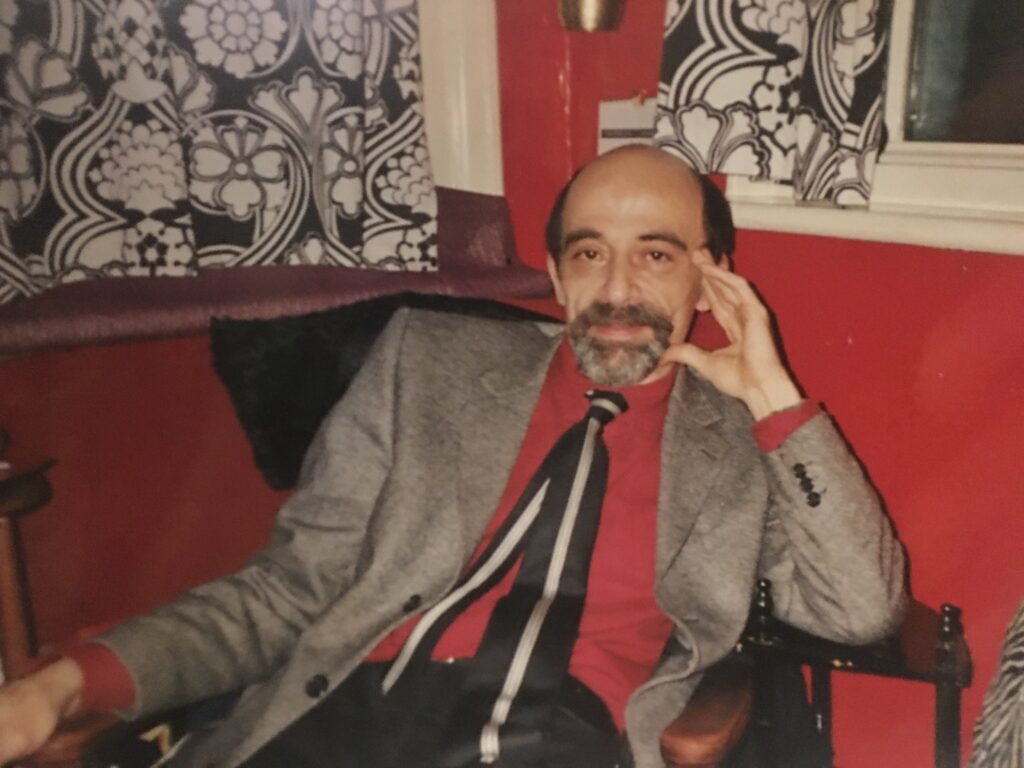

On March 17, 2022, just ten days shy of his 70th birthday, Peter Wilberg, a very unique human being—and a courageous thinker—passed over from the earthly plane to begin what another bold thinker, Carlos Castaneda, called the “definitive journey” that awaits us all. After a long and painful illness, Peter was looking forward to this journey and to the renewed freedom his metaphysical adventures would acquire, once liberated from the body. But he also, up to the end, maintained his characteristically sharp interest in this world. Even during his final days, even when he had little energy to spare, he continued to write about various topics and share ideas with me and my friends about the issues and problems of the day.

Peter was pleased to see the increased attention and understanding forming around perspectives that he had been writing about for decades; though he remained wary of the challenges and roadblocks that will no doubt continue for those applying his kind of deep meditative thinking to the world, especially when this thinking challenged powerful political forces. He thought of himself as a kind of scout from the future sent here to test the readiness of this world for forgotten truths and new ideas.

He sometimes felt that the world was definitely not ready. One can hardly blame him, given the speed with which the whole planet, especially during his last couple years, has seemed to have lost its mind. But he also had to admit that there was new light on the horizon here, even if he was himself, towards the end, ready for the light of a different world.

Our world certainly benefited from Peter’s time here among us. He had that increasingly rare combination of faculties that we need now more than ever: both a brilliantly analytic mind that could see through the false forms that fool most of us, finding unsettling questions amongst even the most sacred assumptions of our culture; but also a spiritual openness to the world as it is, a faith in the presence of a single awareness that embraces all beings and events, imbuing them with meaning and value, no matter how far they may fall into suffering or despair.

And suffer Peter did towards the end of his life, not just from the isolation imposed on him by his bodily circumstances and the escalating culture of confinement of the ill, but often feeling the price of his radical thinking and the marginality such things impose. The new global paradigm, of course, increased and emotionally charged this marginality. Peter lamented how even more readily people jumped to judgment, especially concerning anything like his passion for critiques of medicine. However, he would never dream of backing down, never cease to defend the marginalized ideas he helped give a fuller, richer life with his broad mind.

And this was no mere contrarianism. What Peter saw in fringe ideas and perspectives was no heap of disparate causes with which he could stick it to the man. What he wrote about always came from a deep and coherent sense of truth that led him to critique both mainstream and counterculture confusion when he saw it.

After a popular platitude or misleading idea was put through the wringer of Peter’s critique, an important hidden insight was surely revealed that illuminated a broader and integrated view of all things. Maligned positions and demonized figures were more fairly judged and lifted up to the plane where all seemed to find its proper place in the light of Peter’s vision of a unified field of awareness.

Peter was particularly moved to reconcile the diverse traditions and cultural identities that formed his life and mind. And in his dialog with them in his soul and his work, he helped us all along the way towards healing the split in the soul of Western and global culture—between its traditions and a progressive vision—between an historical consciousness, and a radical openness or receptivity to the new, even new or radical ways of seeing our history and traditions.

But it is Peter’s powerful insights into the unseen consequences and unthought dimensions of biology and medicine that have become crucial perspectives for our contemporary situation, and will no doubt continue to increase in relevance to us all as we become further enmeshed in the biopolitical era.

Through his illness, as tragic and painful as it was, he got to experience in vivid visceral detail the existential tragedy of the paradigm of which he was one of our era’s most astute diagnosticians. As trying as it must have been, I know he found value in the opportunity to further refine his examination of the cruel consequences of dogmatic scientism, and, especially, of the medical machine which he was unable to avoid falling deeply within. Though he sometimes felt this fall into medical dependence as a mistake, he also knew there was a drive in him to experience more fully the object of his critiques.

He and I became close correspondents during his last difficult year or so; I was always interested to hear his daily thoughts and moods as his life and the world affected him and impressed upon him new and fresh insights, even as his illness and medical interventions sapped his strength. We were both pleased to watch a cultural nexus emerge on the internet that brought together and popularized perspectives we both thought were vital and connected, but which had previously languished underdeveloped by serious thinkers, or obfuscated by countercultural excess.

Getting to know Peter at this time was indeed a blessing. We had both independently developed a deep appreciation for not only the spiritual threads linking Eastern and Western philosophical thought, as many do, but also a deep appreciation for more recent contemporary spiritual writers like Castaneda and Jane Roberts, who are mostly passed over by serious thinkers. In fact, when it came to my favorite book, Jane Roberts’ “Seth Speaks”, Peter was the only thinker I could find who recognized its importance and was working to develop and apply its insight.

I came to understand that this fact was symbolic of the most important and dangerous knot of problems in our time: the general inability or unwillingness of philosophers to keep up with or effectively challenge the specific concepts of science that determine our world, along with the concomitant shunting of thinkers that do attempt to challenge specific scientific fields into the margins of culture.

The thinkers of today’s institutions are too specialized and narrowly politicized to see or challenge the big picture effectively. This has been the case for some time, but recent events have only escalated the monolithic force of institutional conditioning, further limiting the extent that, for instance, liberalism, or scientific dogma can be critiqued without severe repercussions.

Consequently, all critiques of science, beyond the generic and politically safe ponderings of humanities departments at universities, happen outside institutions. These critiques get lost in the details, lost in various corners of the internet, unable to spread beyond the various niches of online culture, or the amorphous “cultic milieu” of New Age culture, which lacks a philosophical awareness that could give it some critical focus or political force.

Roberts’ Seth books though, from the moment I first read them as a young man, struck me immediately as very different from what usually gets called “New Age”. Though accessible to the laymen, they carried not only a subtle sophistication, but a keen sensitivity to the philosophical problems of our time. They seemed like a new fount of life for a culture losing its way, though a fount still getting lost or misunderstood by most of the counterculture that did read them or Seth’s more popular imitations.

I found it of vital importance that the best thinkers of today not only engage with the spiritual literature of the past, but help form a new tradition of spiritual and philosophical wisdom for an age ruled by a rapidly changing scientific paradigm that necessitates new critiques. I reasoned that since philosophers had allowed the important innovations in our culture to become wholly dictated and distorted by the shallow thinkers of mainstream science and countercultural pseudoscience, they had set us up for an emerging disaster which we can, in the last couple years, see more clearly.

We can see a splitting of the culture into a more or less educated class, totally beholden to bureaucracy and out of touch with the problems of our day, and a more or less intuitive but easily misled counterculture, educating themselves on the internet or otherwise outside the mainstream.

While there are certainly smart people outside the mainstream, before I found Peter, I was hard pressed to find any with a good knowledge of philosophy. And without philosophy, without a sense of the history of ideas, of the roots and problems of any slant of interpretation, they almost always come off naive, or end up playing to a niche subculture already primed for certain ways of thinking.

Not Peter. He understood this problem deeply. He didn’t play off expectations or shy away from controversy. He critiqued and integrated both sides of everything, showing a way through the stalemate of our contemporary culture war. I was very happy then to find him and his work. For here was a real thinker who not only applied his insight and learning to spiritual matters, he recognized the importance of contemporary spiritual literature, and had been doing his best to further those insights—especially into biology and medicine, which increasingly more people can now see, are becoming crucial to the future of our planet.

Though Peter and I came to many of our insights independently, and given the state of the world, more people are finding their way to similar points of view, he got there first, and spent a good portion of his life developing them in ways I wouldn’t have thought of, and sometimes disagreed with, but always in the context of helpful conversation with him. He never failed to appreciate the magic of dialog.

Along with very few other spiritual writers of our era like Castaneda and Roberts, Peter brought a desperately needed critical clarity and philosophical sensitivity to sincere contemporary writing about consciousness, death, or esoteric issues. Like them, Peter developed his own original thinking and spiritual teaching for our unique times. Peter was most proud of this, especially his development of techniques to aid people in bringing a soulful multidimensional awareness deep into their relationships, where it is most needed, and most often neglected in the frequently self-obsessed contemporary spiritual scene.

But to me, Peter was much more than a spiritual teacher. He was something far more interesting. He was one of a kind. Traditional spiritual teachers, to whatever extent they are not mired by serious problems in our troubled age, may impart wisdom or “healing” to those in their presence, but their explicit influence tends to fade with the passing of their presence, leaving little more than dogmatic adherents that lose the spirit of the teaching.

In preparing for his definitive journey, Peter expressed some concern that his teachings might be lost with his passing. But I didn’t have to remind him that such things were not what really mattered. Explicit influence, big or small, always fades. What lasts—what matters—is what new possibilities of being and awareness we make possible. Peter had the courage to be himself and to think the new, despite the consequences. And in so doing he helped those of us similarly inclined to do the same, to be and think intelligently along lines that are usually ridiculed and repressed—and to do so with confidence that there is value and perhaps something of vital importance to what we are exploring, precisely as the world moves to destroy, assimilate or render innocuous any viral variant threatening its emerging regime.